|

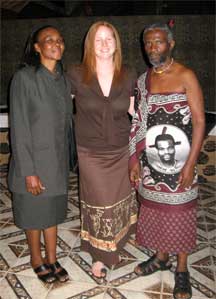

| ±«Óătv student Meredith Copp is flanked by Latsabedze Dlamini (left) and her husband, acting Chief Mzweleni Dlamini. |

When AIDS activist Stephen Lewis addressed graduating social work students at ±«ÓătvĂs convocation last spring, he implored them to spend time in Africa and help a continent fight back against the deadly AIDS pandemic. It isnĂt only doctors and nurses who are needed, he said, but social workers who can help the people left behind get back on their feet.

Meredith Copp didnĂt wait for graduation. Completing the final year of her BSW, the 25-year-old from Lower Sackville, N.S. is spending three months in Swaziland on a field placement.

Talk about a tough assignment. Swaziland is a small country with big problems. ItĂs only been since 2004 that the southern Africa nation acknowledged the extent of the crisis: more than one-third of the population was infected with HIV. Prime Minister Themba Dlamini declared a humanitarian crisis, citing drought, land degradation, severe poverty and HIV/AIDS.

Given the SiSwati name ĂNokulunga Mdluliâ (Ănokulungaâ meaning humble) by her host family, Ms. Copp is working with a non-governmental organization called SWAGAA Ă Swaziland Action Group Against Abuse.

The objectives of the organization are to empower survivors of abuse through counseling and to bring about change in social, cultural and legal systems aimed at protection of women and children against abuse. It also offers support to survivors of HIV/AIDS, helps prepare victims of abuse for court, facilitates self-help groups, and trains peer educators within the schools and members of the communities that are involved in the Lilhombe Lekukhalela program; ĂLilhombe Lekukhalelaâ in SiSwati means a Ăshoulder to cry on.â

Recently, SWAGAA started groups for men.

ĂItĂs realized that in order to eradicate and prevent abuse, they need to get men involved,â writes Ms. Copp in an email interview. ĂThrough this program, the male involvement officer goes out to the communities and facilitates dialogues with the men around gender-based violence in their community, how they want to stop or prevent it, and what cultural

practices are contributing to the violence.â

|

| Members of this self help group are building a small mill for grinding corn in order to create income for the community. They are posing with their graduation certificates. |

But without being able to speak the language and sometimes facing distrust and skepticism because of her privileged Western background, Ms. Copp has had to cope with problems of her own.

ĂI have had some hard times,â she admits. ĂAlthough the place is beautiful and the people are lovely, there are also some really sad aspects. This country is dealing with the worst of the HIV/AIDS crisis. Some people are also extremely poor. There was a drought this year and most of the farmers were unable to get any maize from their crops. More than 400,000 people are starvingĂ

ĂI am also working in an organization that deals with the worst types of abuse on a daily basis. So of course it has gotten to me on a few occasions.â

But there is much joy as well Ă like the mad scramble to catch Ăkhombieâ (the small white vans used as public transit) to get to work; the warm embrace extended by her hostĂs large, extended family and making lifelong friends; involvement in cultural events; and the neighborhood children who trail her, calling out ĂHow are you? I am fine.â

If anything, her experience in Swaziland has given her the taste to do more international social work.

ĂYes, I think that three months may be too short,â she writes. She's expected back in Canada in mid-August. ĂI am almost finished and do not feel ready to go home yet.â