|

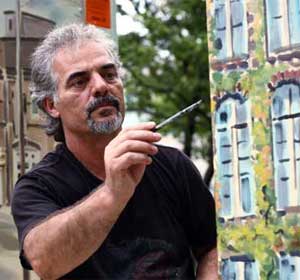

| Zeqirja "Zack" Rexhepi paints the Henry Hicks Building on an Aliant box. (Bruce Bottomley Photo) |

When the paramilitaries came down the street of Zeqirja Rexhepi’s rural village in Kosovo in the spring of 1999, the members of his family scattered and sought out temporary refuge in the mountainside. Gunfire ricocheted through the valley and smoke filled the air from burning houses.

Separated and scared, his six children didn’t know if their father had made it.

“I don’t know if dad is alive or not,” one of his daughters desperately told her mother when they found each other.

Later, people yelling through megaphones brought the villagers down from the mountainsides, telling them they had two hours to clear out. Reunited, the Rexhepi family joined the convoy headed to the Macedonian border. With his children and wife safe and his house reduced to ash, Zeqirja never looked back. When he and his family were offered passage out of the Macedonian refugee camp on a plane bound for Greenwood, Nova Scotia, they seized it.

SEE PHOTOS: An artist's portfolio

All the anguish and fear of living through war came rushing back last week with news of the capture of Radovan Karadzic. The man with the flowing white beard has been wanted for 13 years on charges on genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.Â

But as quickly as bitter feelings arose, they subsided. Now when Zeqirja talks about Karadzic and his role in the war that tore apart the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, he feels pity.

“Look what he did. He destroyed his life and the reputation of his country,” says Zeqirja or “Zack” as he’s known by coworkers at ±«Óătv. “He has been hiding from his own name.”

Mere months after 5,000 Kosovar refugees arrived in Canada in May 1999, many of them opted to return home. Serbian forces had been driven out of Kosovo and the UN took over its administration. (Kosovo just recently declared itself independent from Serbia. Prime Minister Hashim Thaci has pledged a democracy that respects the rights of all ethnic communities. Canada, the United States, Japan, Britain and some 40 other nations have recognized Kosovo’s move.)

But the Rexhepi family was already home: the children, then aged eight to 19, were learning English, making friends and adjusting to school; his wife Bea started a hair salon; and Zeqirja, a painter and textile designer in his native Kosovo, was picking up design work for movies and TV and establishing a reputation as a muralist. The classically trained violinist even got a gig playing Celtic fiddle in a play at Ship’s Company Theatre in Parrsboro.

He’s relieved to leave behind freelancing since getting hired at ±«Óătv Facilities Management as a painter two years ago —four of his kids are studying at ±«Óătv—while devoting his spare time to his art. He paints, teaches art classes and continues to do commissions. For Aliant, for example, he recently painted the utility boxes on the boulevard of University Avenue at Robie Street with ±«Óătv scenes.

One of his favorite commissions was a portrait of Joseph Howe, for the 200th anniversary of his birth in 2004. After doing research for the portrait, he came to admire the newspaperman for his impassioned defense of freedom of the press and his dogged work to bring responsible government to Nova Scotia in 1848.

“I wanted to paint his spirit,” says Zeqirja, who became a Canadian citizen in 2004. “He is one of the reasons Canada is such a great place. There is freedom and democracy and equality. You don’t know how much that matters until you live in a place without such things. Like now, here we are sitting and talking. We have no worries. It is not the same in other places.”