|

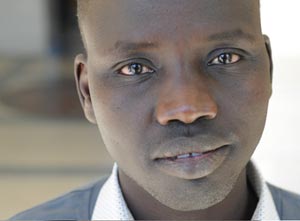

| John Kon Kelei: "You just keep hammering on about what you don't like to talk about." (Danny Abriel Photo) |

John Kon Kelei hates to talk about it. But the experience of being a child soldier in Sudan is one he shares with anyone who will listen.

“You just keep hammering on about what you don’t like to talk about,” says Mr. Kelei, wrenched from his family by an armed group when he was just five years old. Too little to be of use in battle, he was put to work cleaning weapons, gathering firewood and acting as a look-out.

A co-founder of the Network of Young People Affected by War (NYPAW), Mr. Kelei is at ±«Óătv for two days of workshops with the Child Soldiers Initiative, managed by the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies. Participants will be looking for ways to ease the transition for Sudanese youth who come to live in Canada and are often sucked back into violence and crime.

|

Joining the participants  (Sudanese youth, police, immigrant settlement workers, academics) for the workshops will be Mr. Kelei’s friend, rapper Emmanuel Jal.

Called an artist “with the potential of a young Bob Marley” by Peter Gabriel no less, the musician will also talk and perform some of his original music at a public event, Thursday, September 23, 8 p.m. at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium. Also performing are spoken word artist El Jones and dance-hall reggae performer Saa Andrew.

|

The two have much in common. For example, they can only guess at their own ages. Mr. Jal estimates his birth as January 1, 1980, although he doesn’t know when or where he was born. Mr. Kelei gives his age as 27, “but I don’t really know,” he says with a shrug. Neither the government forces or the rebels took much notice of birthdays.

Both men have emerged as advocates for child soldiers, kids who are forcibly recruited or enlisted in hostilities throughout the world. While there are international laws and policies prohibiting the use of child soldiers, enforcement is lagging, says Shelly Whitman, deputy director of the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies. It’s estimated there are 250,000 child soldiers today.

For Mr. Kelei, the realization that “keeping quiet is not an option” came to him as a scared 17-year-old boy who had made his way to the Netherlands after fleeing the Sudan.

He recalls his first night in asylum in Amsterdam, where he was shown a spartan room, furnished with a single bed covered by a white sheet.

“It was,” he recalls, “the most luxurious place I’ve ever been.”

As he lay awake that night, starring at the ceiling, he was plagued with guilt over the boys still bearing arms in his homeland while there he was, “tasting the best of life.”

That’s when he made his resolution: “I will talk about my past ... Keeping quiet is not an option.”

LINKS: |