|

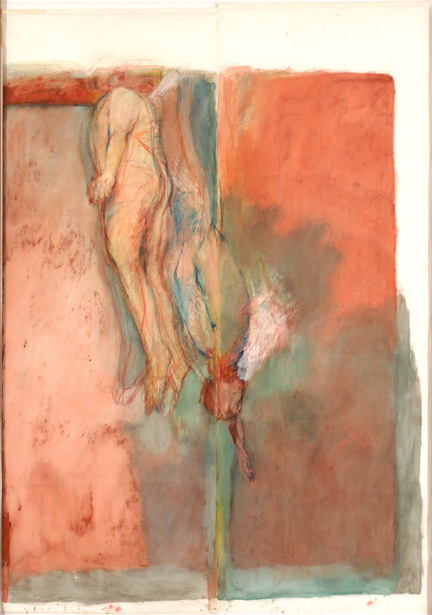

Betty Goodwin, Red Sea, 1984, collection: Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal, photo: Richard-Max Tremblay. |

The serene bell-jar atmosphere of the ±«Óătv Art Gallery frames its current exhibit, Betty Goodwin: Darkness and Memory, perfectly. Where and how a person views art can be as vital to the experience as the pieces themselves, and although a temporary exhibition, the aptness of Goodwin’s work’s surroundings (meditative, uncrowded) to its subject matter (brooding, mysterious) suggests the studied situation of a permanent exhibit. If you’re going to see Betty Goodwin’s work, the Dal Art Gallery is the place to do it—and her work certainly should be seen.

Josee Belisle (curator of the permanent collection at the Musee d’art contemporain de Montreal) writes of Betty Goodwin: “Her work probes the labyrinth of the subconscious to explore problematic questions of suffering, death and oblivion… Betty Goodwin persistently re-examined the objects that shape our time and our passage through the uncertain territories of existence.”Â

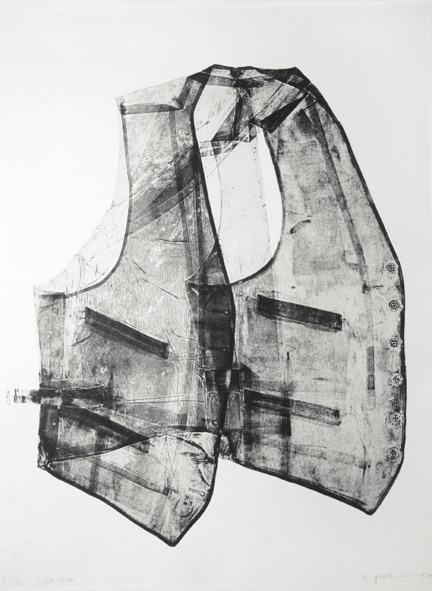

The artist was a Montreal native, and died only three years ago; however, despite the fact that much of the work in Darkness and Memory is 40 years old or even older, much of it suggests a not exclusively pessimistic fixation on mortality. Some of her art, for instance, plays with notions of quintessentially human artefacts as divorced from human usage. Gloves One (1970), Vest Two (1970) and Two Vests (1970) all examine the titular items of clothing as removed from the human form. Shirt with Flower (1972) pushes even further, placing a pressed flower where the heart of the shirt’s owner would be, thus inviting audiences to consider the properties of these garments once freed from the context of a wearer.Â

Betty Goodwin was fascinated with the human body—represented not only via the traditional paints, paper and ink, but as in La Memoire du Corps (1992), tar, graphite, and oil stick. La Memoire du Corps depicts a cloudy shape, like a hand or a human body, suspended in space above a blocky black shape; a reddish tinge in the image suggests blood. She addresses the riddle of the stretched, almost distended human body again in Untitled (Nerves) No. 5 (1995), in which the prostrate, blurry form lies of a bed of white lines (nerves? Sticks? Something more sinister?). Furthermore, Goodwin does not allow herself to be hampered by realism in depicting the active human form. In her Swimmers (1983) two blurred forms, posed to suggest underwater movement, reside on a background as dark as that of La Memoire du Corps; again, they are juxtaposed with a red stain which seems to suggest blood. The motif of strange red stain is echoed again in Red Sea (1984), perhaps the largest piece in the exhibit, and one dealing again with bare bodies.

|

Betty Goodwin, Vest Two, 1970, collection: Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal. |

Despite her clear fascination with the human form, Betty Goodwin did not work exclusively in conventional, two-dimensional images. Tombeau de Rene Crevel (1979-1980) consists of delicate prints of the poems and design work of Paul-Marie Lapointe (perhaps in future the Musee d’art contemporain de Montreal, which organized the exhibit, might consider providing a translation for visiting Anglophones). Bound Voices (1997-1998) does not even primarily concern itself with visuals. It is a wire-bound pole attached to an old-fashioned “Discman”-type CD player; whispery voices issue from the pole, but no words are especially coherent. She also works comfortably within the parameters of abstractionism, as in the uncompromising Dessin no. 8 (1981), Passages (1981) and River Bed (1977). Sometimes her more esoteric work verges on the playful, as in Tarpaulin no. 2 (1974-1975), which appears to be, basically, a patched tarp hung on a wall. Asking what Tarpaulin no. 2 means or signifies is tempting, but a slippery slope to take when faced with art as challenging and remote as Goodwin’s. A better (if frequently neglected) approach is simply to think about it—and the Dal Art Gallery is the perfect place for thinking.

Betty Goodwin: Darkness and Memory is on display at the ±«Óătv Art Gallery, located on the lower level of the Dal Arts Centre, to Sunday, March 6. Gallery hours are Tuesdays to Fridays, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturdays and Sundays, noon to 5 p.m. Admission is free.