Athanasius ‚ÄúTanas‚ÄĚ Sylliboy, RN and graduating Master of Nursing ‚Äď nurse practitioner student, is in his community of Eskasoni, working hard to minimize the impact of COVID-19.

Tanas graduated from Cape Breton University with his Nursing degree. He says he and a fellow classmate were the first two Mi'kmaw men to graduate from CBU’s nursing program.

After doing a placement with a nurse practitioner, Tanas realized he was very interested in pursuing that career ‚Äď and believed it would be beneficial to his community in Eskasoni.

‚ÄúWhen I was working as a nurse here, a physician said it would be interesting to see a Mi'kmaw provider in the community. The biggest thing is compliance and understanding the severity of an illness. Community members often tell me, when your own people tell you, you take it to heart and listen. I‚Äôm telling them in our own language, so things are understood and don‚Äôt get lost in translation.‚ÄĚ

į¬≥ůĪū≤‘Őż, Tanas thought that would be the perfect time to apply.

Throughout the program, Tanas worked in the Emergency Room at the IWK Health Centre and was a part-time clinical researcher with the Aboriginal Children’s Hurt & Healing Initiative through the same hospital.

Those experiences led Tanas to his current job as a nurse practitioner in Eskasoni. He works with primary care providers at a health centre that houses community health, primary care, home care, diabetic care and pharmacy care.

Community care during COVID-19

‚ÄúThe day they announced our first case in NS, I was like ‚ÄėOkay it‚Äôs happening, I need to do something‚Äô. Completing my hours is important but I wanted to minimize the impact of covid19 through education and resources. It‚Äôs not even doing work or volunteering, it‚Äôs my responsibility to do what I can to help.‚ÄĚ

Tanas immediately thought about the home care clients in his community who would be high risk of severe symptoms if they contracted COVID-19. He got to work to create awareness, and started making posters on his phone.

Tanas immediately thought about the home care clients in his community who would be high risk of severe symptoms if they contracted COVID-19. He got to work to create awareness, and started making posters on his phone.

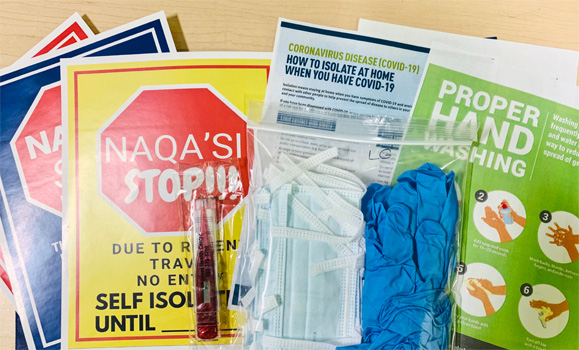

‚ÄúIn our community we already put signs on doors if someone if undergoing treatment, to say please don‚Äôt come in or please wash hands on entry. Naqa‚Äôsi, the word for stop. I created posters that warned others, this household has high risk members.‚ÄĚ

Tanas posted them on Facebook and emailed different Mi’kmaw health directors to ask them to disperse them to other communities. He started to get requests to make signs that say certain things in different languages. People in Sydney, NS made their own and thanked their Eskasoni neighbours for sharing the idea.

Creating care packages

Tanas and his team started making care packages for people self-isolating which include informational packets and thermometers. Tanas wanted to make sure there was awareness and education for everyone returning home from March Break or international travel, and as policies changed, coming in from out of province.

Őż

Őż

In addition to the packages, Tanas and his team also did wellness checks, calling people to check-in on how they were doing.

‚ÄúIt could take several hours to call just six people. Calls were informational, but also social ‚Äď people would share stories of coming back home, saying one minute they were in Florida, next minute they are home alone.‚ÄĚ

Self-imposed lockdown

Tanas and his team are working with anyone with symptoms to try to minimize transmission in their households and how to avoid leaving their house.

, and people cannot enter or exit except for essential services. Tanas ends up working 12 hours some days to make sure everyone has what they need.

‚ÄúWe make arrangements for the community grocery store to deliver to people, and call them and let them know it‚Äôs there. With groceries, the social aspect and any other errands like banking ‚Äď we‚Äôre fortunate in Eskasoni that we work really well together.‚ÄĚ

Tanas says the measures may seem extreme but if COVID-19 hits Eskasoni it would hit hard because people live in close proximity ‚Äď sometimes seven-eight individuals per household with people living with parents or grandparents ‚Äď and the amount of chronic disease in the community.

‚ÄúThere was some hesitancy and backlash from the community at first but once the province started having increasing cases of COVID-19 it was clear the measures were called for.‚ÄĚ

There is no testing centre in the community, and Tanas says transportation is a barrier regardless of COVID-19 or not. They transformed their community van to a COVID-19 van so it’s sealed off from the driver, and the passenger sits in the back when they need to get tested.

Engaging with the community

Tanas says the information coming from the government is in English and French, so he and his team are creating videos to provide it in Mi’kmaq as well. That includes a handwashing video created by community members with clips of them singing Amazing Grace in Mi’kmaq. The video has been shared in Eskasoni as well as other communities. Tanas says it was educational but also made people feel peaceful.

Tanas says they are trying to really get the point out that this is serious.

‚ÄúThere is a word in Mi‚Äôkmaq, Mukk mali-ksua'tup, that means don‚Äôt underestimate it. If you don‚Äôt take it seriously it will take you seriously.‚ÄĚ

The clinic youth workers are interacting with young people in the community through social media and a television challenge and doing different challenges like drawing or TikTok to keep people engaged.

‚ÄúA few weeks ago it was chaos. Now there‚Äôs an understanding that things are going to be like this for a while. It‚Äôs not normal but it‚Äôs okay.‚ÄĚ

Tanas is on track to graduate in May, as he was able to finish his clinical hours before research activity was halted. Working right after graduation wasn’t what he had planned, but he is glad to be able to help.

‚ÄúI wouldn‚Äôt have it any other way, I‚Äôm doing everything I can to support our communities and other Mi‚Äôkmaq and First Nations communities.‚ÄĚ