Feared by most and loved by some, sharks play a critical role in our ecosystem and are an important economic resource to many communities and countries. With Shark Week 2021 now underway, let’s demystify some of these species.

Meet your neighbourhood sharks

There are a few shark species that can commonly be found in waters off of Nova Scotia.

Porbeagle Shark

The Porbeagle Shark is one of the most cold-tolerant shark species in the world, preferring water temperature colder than 18 degrees Celsius. It also spends most of its time in Canadian waters.

The Porbeagle Shark is one of the most cold-tolerant shark species in the world, preferring water temperature colder than 18 degrees Celsius. It also spends most of its time in Canadian waters.

It is a stout shark with large eyes that help spot its prey. It is bluish or brownish-grey on top and white underneath with a white patch on the trailing edge of the dorsal fin. It has a crescent-shaped tail and a secondary keel that effectively cuts the water during the side-to-side motion, making its swimming more efficient.

·������������ Life span: Estimated to be between 25 and 46 years

·������������ Size: Up to 3.7 metres (12 feet)

“The porbeagle is a warm-bodied shark that hangs around all year long,” says Fred Whoriskey, executive director of the Dal-hosted Ocean Tracking Network. “They have been known to create some exciting moments for cage divers who are off of the fish farms in places like Digby. When they are trying to take care of the cages and clean them in the winter, suddenly there will be these big sharks flying by.”

(Above image from Ocean Tracking Network)

Greenland shark

The Greenland shark is one of the largest sharks in the ocean. Though both large and predatory, this species is not known to be particularly aggressive towards people and is thought to be fairly sluggish in the cold waters of the north Atlantic Ocean. But then again, it is rare that people swim at the temperatures this species likes, so those who do spend time in the water with the animal are encouraged to treat it with great respect. The colouration of the shark varies slightly; adults can be brown, black, purplish gray or slate gray, while the sides may have a purple tinge, or may have dark bands or white spots.

The Greenland shark is one of the largest sharks in the ocean. Though both large and predatory, this species is not known to be particularly aggressive towards people and is thought to be fairly sluggish in the cold waters of the north Atlantic Ocean. But then again, it is rare that people swim at the temperatures this species likes, so those who do spend time in the water with the animal are encouraged to treat it with great respect. The colouration of the shark varies slightly; adults can be brown, black, purplish gray or slate gray, while the sides may have a purple tinge, or may have dark bands or white spots.

It inhabits arctic and subarctic waters where temperatures hover between -2 and 7 degrees Celsius, and it the only shark species found regularly in these cold waters. The Greenland shark is a deep dweller, and commonly found at depths greater that 200 metres, but it comes to the surface during the cooler winter months and will move into very shallow water in places like the high arctic when prey like newborn seals are around.

·������������ Life span: At least 250 years, with some living more 500 years.

·������������ Size: 7.3 metres (24 feet)

“The further north you go, the more of them you find,” says Dr. Whoriskey. “The further south, when you get into warmer waters, they go deeper, and it is harvesters fishing deep lines in these areas that get to see them.”

(Above image courtesy of Brittanica)

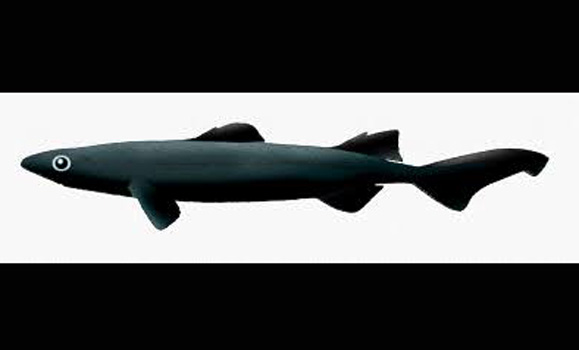

Black dogfish sharks

The black dogfish is a small deep dwelling shark with a short and heavy-set body. Both of the dorsal fins have white spines on the leading edge. As the name suggests, this shark is completely black with the exception of the white dorsal spines. Older individuals may be a dark chocolate brown.

The black dogfish is a small deep dwelling shark with a short and heavy-set body. Both of the dorsal fins have white spines on the leading edge. As the name suggests, this shark is completely black with the exception of the white dorsal spines. Older individuals may be a dark chocolate brown.

In the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, the black dogfish can be found off southern Greenland and Baffin Island, continuing to waters around Labrador, on the Scotian Shelf, and Georges Bank. Its range continues down to Cape Hatteras and possibly to Florida and into the Gulf of Mexico. It is common in deep waters of some areas, such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

·������������ Life span: Estimated to be 35-40 years

·������������ Size: Roughly 0.6 meters (1.9 feet)

“We actually have a Marine Protected Area developing in the Cabot Strait that is there to primarily protect the black dogfish,” says Dr. Whoriskey. “What’s needed now is the kind of work that would go on to determine not only if the MPA is working effectively to take care of the black dogfish — in other words, do they use it a lot, do they stay within the borders, are they being protected over time – and just to understand their basic biology.”

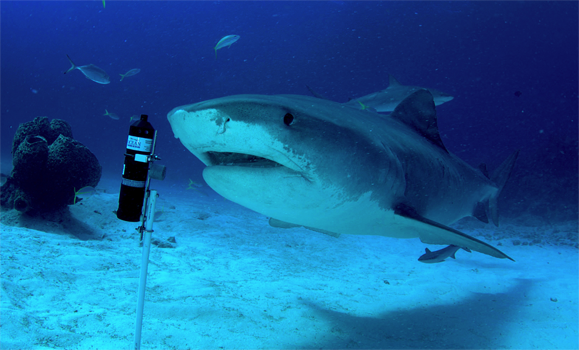

Dr. Whoriskey notes that there are also tropical species, such as the tiger shark, that are moving north in pursuit of food; great whites, blue and other seasonal sharks found in regional waters during the summer.

(Above image courtesy of the University of Guelph)

Be “shark smart”

It is believed that most unprovoked shark attacks are cases of mistaken identity. In fact, Canada’s last unprovoked attack on the east coast was back in the mid-1800s, and it was against a dory in the offshore area.

“When this happens, water visibility may be poor and all the shark sees from the human in the water is a silhouette or a flash that it identifies as a potential fish or marine mammal prey,” says Dr. Whoriskey.

Even though unprovoked attacks are rare, shark populations are growing, and some species may be moving into areas they had not inhabited before, or for a very long time. We need to do our part and reduce the risk of unexpected encounters.

“That means not venturing out into the water at times when sharks may be hunting for food, like at dusk, or being in areas where there are seals,” says Dr. Whoriskey. “Think of it like a bear, a wolf, or a bobcat that may be present when you go for a hike in a national park. These are wild animals that need to be treated with respect, and the ocean is their home.”

(Above, a tiger shark investigates an OTN station deployed by the University of Miami collaborators in the Bahamas. Jim Abernethy photo)

Surprising shark facts

(Curated by our friends at the , or NOAA)

·������������ Sharks do not have bones. They are a special type of fish known as “elasmobranch,” which translates into fish made of cartilaginous tissues — the same stuff that your nose tip and ears are made of.

·������������ Most sharks have good eyesight. They can see colours and have fantastic night vision. The back of their eyeballs have a reflective layer of tissue that helps them see well with little light.

·������������ Sharks have special electroreceptor organs. The small black spots near the nose, eyes and mouth allow the shark to sense electromagnetic fields and temperature shifts in the ocean.

·������������ Shark skin feels similar to sandpaper. This is because it’s made up of tiny teeth-like structures called placoid scales, which help reduce friction from surrounding water when sharks swim.

·������������ Sharks have been around for a very long time. Based on fossil scales found in Australia and the United States, scientists hypothesize sharks first appeared in the ocean around 455 million years ago.

·������������ One way scientists age sharks is by counting the rings on their vertebrae. Vertebrae contain pairs of opaque and translucent bands. Band pairs are counted like rings on a tree. However, recent studies have shown that this assumption is not always correct. Each species and size class must be studied to determine how often the band pairs are deposited because the deposition rate may change over time.

·������������ Blue sharks really are blue. The blue shark displays a brilliant colour on the upper portion of its body and is normally snowy white beneath.

·������������ Each whale shark’s spot pattern is unique as a fingerprint. Whale sharks are the biggest fish in the ocean. They can grow up to 12.2 meters and weigh as much as 40 tons by some estimates.

·������������ Some species of sharks have a spiracle that allows them to pull water into their respiratory system while at rest. Most sharks have to keep swimming to pump water over their gills.

·������������ Not all sharks have the same shapes and structure to their teeth. Mako sharks have very pointed teeth, while white sharks have triangular, serrated teeth. Shark teeth are also lost on a regular basis, and the animals grow new ones. For example, a sandbar shark will have around 35,000 teeth over the course of its lifetime.