The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, 1984 by George Orwell, Beloved by Toni Morrison — these are just a few of the famous works of literature that have found their way onto banned books lists in different countries and jurisdictions over the years.

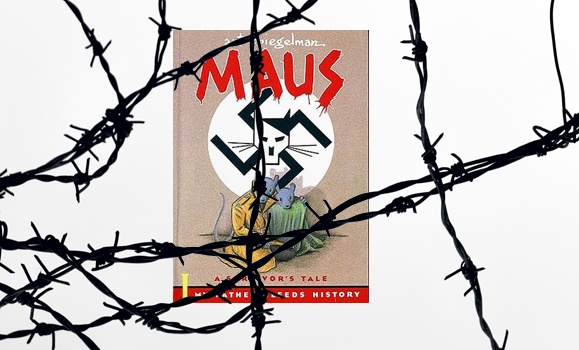

The battle over what people can and can’t read is as old as publishing itself and remains a fraught and contentious issue as a recent example in the United States shows. In January, a school board in Tennessee from its shelves. Art Spiegelman’s 1986 book about the Holocaust was deemed unsuitable for eighth-grade curriculum based, in part, on its use of foul language and illustrations depicting nude figures of mice and cats.

The controversial move has opened up a far-reaching dialogue among scholars about the ethical implications of such a decision. With the , some individuals are left with more questions than answers. Book banning itself is a complicated process, mainly because of the ethical questions that are raised regarding the importance of access to information and the right to freedom of expression when weighed against the harm that a challenged book could have on certain groups.

The controversial move has opened up a far-reaching dialogue among scholars about the ethical implications of such a decision. With the , some individuals are left with more questions than answers. Book banning itself is a complicated process, mainly because of the ethical questions that are raised regarding the importance of access to information and the right to freedom of expression when weighed against the harm that a challenged book could have on certain groups.

(above left), dean of at ±«Óătv, has years of experience navigating tricky topics in the field and represents Dal Libraries on local and national boards. She spoke to Dal News to provide some insight into this highly charged and divisive topic.

Why are books banned in the first place?

Those who attempt to ban books do not agree with the views espoused in the books, and they believe the ideas in the books will influence those who read the books in ways with which the book banners do not agree. In general, book banning can narrow the perspective available to society, to that of those in power. It limits dissenting or alternative views and enforces a system of privilege.

Is book banning an effective practice in certain situations?

I can’t think of a time when book banning has been an effective practice, for any book that is legal. Most books that are banned have been legally published and acquired by libraries or schools and have been mindfully added to a collection to contribute to a broad, unrestricted perspective on all topics. Those seeking to ban the books are individuals with an intellectual, religious, or political agenda that is counter to the contents of the book. They believe they are protecting others, but often they are making decisions on behalf of others that reduce opportunities for access to knowledge.

Where is the line between freedom of information and protection of harm?

This is a question that has become more complex over time. Even a decade ago, I would have said that if the material was legal, it should be on the shelves. More recently, additional considerations about protection from harm have been introduced into the professional and political dialogue. My personal concern is that any consideration beyond whether a book is violating any laws becomes subjective — how do we define “harm” and who decides what will potentially cause harm?

If a book is illegal, the decision is easy. Things become challenging when we have a book that falls in a grey area where it may be promoting something like hate crimes, but the book itself has not been found to be illegal. While some of us would be tempted to agree a book like this causes harm and should be banned even if it has not been found to be breaking any laws, these are the same thought processes that have been used by others to remove books on contraception, sexuality, critical race theory, history, feminism, etc. Equity, diversity and inclusion are not possible when one is banning books, even though sometimes a book is challenged due to EDI-related concerns. Once a decision to remove a book is based on anything other than legality, it can lead to more and more titles being banned on subjective grounds.

What kind of impact does book banning in other countries have in Canada?

I’ve heard anecdotes about how book banning in the U.S. has bolstered business for some publishers and bookstores in Canada, over the last century. On a more somber note, when the incidents of book banning are as prevalent as they are currently in the United States, there can be a chilling effect in Canada, if librarians and others start to anticipate opposition to certain titles, and act on that fear of confrontation by not selecting the more controversial titles. One certainly hears about book banning, and censorship of information in general, by the government in power in many countries, which reduces the ability of citizens to obtain information or fully participate in a democratic society.

Are there any books that ±«Óătv will not carry under any circumstances?

We wouldn’t carry books that are illegal, and beyond that, we try to collect as widely as possible. When there is the potential for harm, for instance with some titles that have historic value but portray dated, racist or untrue depictions of people or cultures, we do attempt to provide some context for the title and make it clear the value is historic, though the content is offensive. We might put the book in Special Collections or the Archives, to denote historic value. Book banning generally runs counter to EDI initiatives, but some books that are challenged do not support EDI efforts, like titles that include historic and now biased colonial viewpoints. When titles like these remain in library collections, it is important to consider how they are presented.