The headline arrived in early September as the haze finally began to clear on Canada's worst wildfire season on record: a are worried about climate change.

And nearly three quarters of those surveyed in the national poll by Leger said they believed extreme weather events are linked to these changes.��

What the responses also revealed, though, was that only a small faction of those polled listed the climate crisis as the top issue facing the country. A majority cited inflation, housing affordability, and interest rates as top concerns.

When there is so much to worry about, so many crises competing for resources and attention, can Canada and other democracies actually meet the collective challenge of climate change?

That's the question Jeff Douglas��(BSc'93), CBC radio host and Dal alum, and three of Canada's leading experts in climate policy and politics set out to interrogate during this year's Stanfield Conversation. The panelists were:��

- Megan Leslie (LLB’04), former NDP Member of Parliament for Halifax for two terms and current��President & CEO of World Wildlife Fund-Canada

- Naheed Nenshi, former mayor of Calgary for three terms and consultant on urban issues

- Mark Jaccard, distinguished professor of resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University and current chair and CEO of the British Columbia's Utilities Commission

While all three expressed optimism that democracies can rise the challenge, the night's wide-ranging discussion made it clear that it won't be easy. The bottom line: For Canada and other democracies, fighting climate change will require a lot more effort from politicans and citizens alike.��

Learn about some highlights from the discussion below and watch the full event at the bottom of this article:

Attendees listen in to the conversation in Dal's Joseph Strug Concert Hall.

Doubling down on democracy

Every four years or so, Canadians head to the polls to cast a vote for the individuals they see as best placed to represent them and their communities in Canada's national parliament. They do the same at the provincial level and in their local municipalities from time to time.

But is this practice — the hallmark of representative democracy — enough to keep citizens engaged and enough to ensure elected representatives are equipped to meet the challenge of issues such as climate change?��

Megan Leslie doubts it.

"Democracy can meet these challenges, but we need more democracy, deeper democracy. We need participatory democracy," said Leslie.

Megan Leslie.

Politicans are just people and "actually do need our help" to come up with solutions, she explained. The problem lies in our current political arrangements, which can make this tough — especially when many policies (carbon taxes, for example) alienate people with overly complex, technocratic approaches.

Instead, she said we need a shift to discussing climate in terms of how we can meet people's basic needs. People might want to live in a community that is protected from flooding, where there is access to climate-mitigating nature nearby, and where they can adopt green technology into their everyday lives and feel like they are part of the solution.

Developing policies to match these community values can be a winning combination, said Leslie.��

One size doesn't fit all

Unless, of course, other people and politicians don't share these values — a definite risk in a large decentralized, democractic country like Canada whose economy relies heavily on its massive energy sector.

Singling out fossil fuels coming from Alberta as an easy win on the road to meeting our climate targets, for instance, could backfire given how tied the industry is to people's everyday lives.

"We have to realize these are people's lives and people's livelihoods,"��said Naheed Nenshi, noting that shutting down an entire sector of the economy would have dire consequences for building democratic consensus on climate change and would likely turn people off the issue altogether.��

Naheed Nenshi.

Getting people onside is important but hard to do in a climate where political rhetoric is so severe, so 'us and them,' said Nenshi. He raised the example of some jurisdictions in Alberta and Nova Scotia that are poorly impacted by federal climate policies and how Ottawa has failed to engage in conversation in pursuit of a greater overall progress.

"Where's the flexibility? Where's the understanding that we might have to move at different paces on this piece . . .�� to move more quickly on something else? I believe as reasonable people, we should be able to get there and have this conversation," he said.

Support climate-sincere politicans

Politicans in modern democracies like Canada can sometimes seem obsessed with short-termism and flavour-of-the-month priorities, always looking for ways to score political points, dodge hot potatoes and ensure they've got support to succeed at the polls.

In such a political environment, it can be tough to sort out who takes bigger, longer-term priorities like climate change seriously. But it's worth putting in the effort to find and support them, argued Mark Jaccard.

Mark Jaccard.

Typically, a climate-sincere politician will have an approach to pricing carbon, some ideas around regulating electricity, transportation and building, and then policies for engaging industry. Jaccard says they'll also have climate targets, but may not tell you about the policies to reach those targets.��

“We should all have a bit of empathy for climate-sincere politicians. It’s not like they’re just bozos out there where they're not listening to anybody. They are facing enormous constraints," he said.

Jaccard said there are independent groups in Canada now that track politicians' approaches to the climate crisis, meaning it's not so hard to find them.

"Then you'll probably need to learn in our Canadian system to vote strategically," said Jaccard, to a shudder from Megan Leslie — who said her own political career as an NDP MP came to an end during the 2015 election due to the practice.

Building engagement

One of the most prevalent threads of the evening's conversation — as hinted at in comments shared above — revolved around how to build engagement on climate, key for tackling the issue in a system where politicians derive their power from popular support.

Jeff Douglas placed the issue in stark relief at one point: "Some people are working two jobs and considering going to food banks for the first time in their lives," he said, also mentioning systemic racism as another major issue facing people.��“What’s the argument for them to engage on an issue like climate?”��

Jeff Douglas.

Leslie furthered her point about tying climate goals to meeting people's basic needs through making energy more affordable or making it easier to acquire different modes of transportation. "A community can come together when it sees itself in policies," she explained. "That’s when community looks and says, 'Oh, that’s something I should be a part of.'"

Nenshi said if he were still a politician — 'no,' he joked in mock response as if been asked if he'd ever return to politics�� — he would be trying to engage people in a broader conversation about what's possible rather than a conversation about what's being taken away from you.

Jaccard said to succeed on climate change likely requires us to draw more attention to successes. He mentioned various examples throughout the night, including B.C.'s policy for getting more electric vehicles on the road — an approach that has led to a 20 per cent boost in sales over a year. He explained how Sweden and Denmark, both also liberal democracies, have made massive strides in zero-emissions building.

Related reading:��CBC Radio host and alum Jeff Douglas returns to Dal to moderate 2023 Stanfield Conversation

The Rt. Honourable Joe Clark, former Canadian Prime Minister, and the Honourable Anne McLellan, Canada's former deputy prime minister and former Dal chancellor.

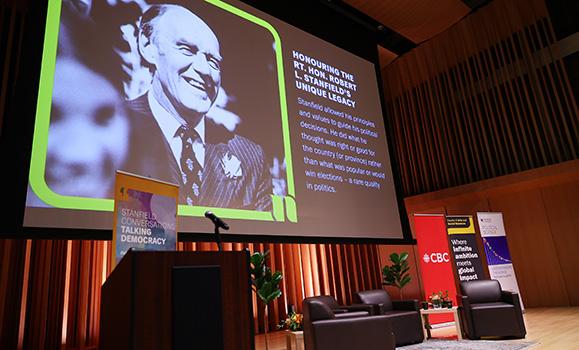

An image of the Right Honourable Robert L. Stanfield, the annual panel series' namesake.

Megan Leslie, Naheed Nenshi,��Rt. Honourable Joe Clark, the Honourable Anne McLellan, Dr. Mark Jaccard, and Jeff Douglas.