When thinking of what lies in the depths of the Bedford Basin, ancient shipwrecks might come to mind or perhaps the fleet of damaged Volvos that was unceremoniously dumped in 1969. While not possible to visualize without a microscope, our waters are also home to scientific discovery: Dal researchers have identified a type of bacteria local to Halifax that could help scientists better understand the health of the ocean.

Named T. haligoni in honour of the city where it was found (its full name is Candidatus Thalassolituus haligoni), this bacterium is what’s known to biologists as a diazotroph or nitrogen fixer — a kind of “fertilizer of the sea,” according to Sonja Rose, a Dal PhD candidate in biology who worked on the research.

Rose, who was the lead author on a research paper about the discovery published this summer in Science Advances, explains that nitrogen is an essential nutrient in the survival of all living things. Nitrogen fixers serve as fertilizers by taking nitrogen that has dissolved in the seawater, which algae (such as phytoplankton) cannot use, and turning it into a form of nitrogen (ammonia) that algae can absorb and grow with.

“Diazotrophs in the terrestrial realm, like a bean plant, help plants and the surrounding soil community,” says Rose. “It’s similar with T. haligoni, but in the ocean. It helps phytoplankton, which in turn helps whales and krill. The process of nitrogen fixation helps the algae get the nitrogen they need to grow, almost like a natural fertilizer.”

Bedford Basin sampling collection in Tufts Cove with Dr. Jennifer Tolman, Ella Kantor, and Sonja Rose. (Dr. Jennifer Tolman photo)

A discovery made in Halifax

T. haligoni was first identified in the Bedford Basin in 2014, predating Rose’s arrival as a PhD student. Rose began studying the bacteria and building on the work started by her predecessors in Dr. Julie LaRoche’s Marine Microbial Lab during an honours project in 2017 and continued after beginning her doctoral studies in 2018.ĚýĚý

“Sonja really owned the project,” says Dr. LaRoche, the Canada Research Chair in Marine Microbial Genomics and Biogeochemistry (Tier 1) and a professor in the Department of Biology. “Sonja spent many long hours in the laboratory to figure out how to grow it efficiently and it paid off.”

“We didn’t really know how it grew or what it likes to eat,” says Rose. “We didn’t have a full genome picture.”

The decade between the discovery and the publishing of the research paper, which was co-authored by Rose’s co-supervisors Dr. LaRoche and Dr. Erin Bertrand along with several other collaborators, represented an opportunity to provide a more complete picture of T. haligoni’s characteristics.

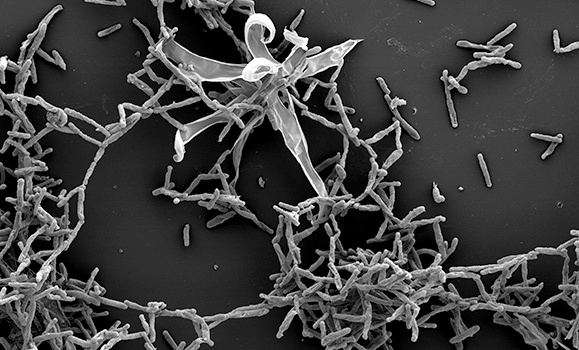

Shown right: Zoomed image of scanning electron micrograph of T. haligoni under nitrogen fixing conditions obtained from the electron microscope facility in the Sir Charles Tupper Medical Building. (Colour edited by Dr. Brent Robicheau).

While first identified in Halifax, the microbe has a global distribution, meaning it can be found across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans.Ěý

“We have a model species for a very important ocean nutrient: nitrogen,” says Rose. “By understanding how this species behaves, we can have a better understanding of our ocean health.”

Dr. LaRoche says the discovery helps address a “really significant knowledge gap concerning this type of marine microbe.” “Diazotrophs that are not also algae have been elusive to isolate and grow in the laboratory, “she says. “They are widespread and diverse and their role in the ocean is poorly understood.”

±«Óătv and the Bedford Institute of Oceanography (BIO) have long been collaborators on the Bedford Basin Time Series, a weekly collection of samples for research purposes, and T. haligoni is further evidence of the scientific possibilities contained in the Bedford Basin.Ěý

“I think everyone in Halifax should be very proud of the exciting research that’s happening in our own backyard,” says Rose.