News

» Go to news mainFair but Formidable

This story originally appeared in theÌę2024 edition ofÌęHearsay, the Schulich School of Lawâs Alumni Magazine.

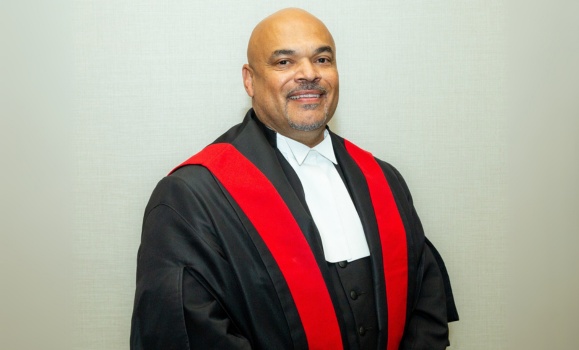

In law school, Perry Borden (â02) dreamed of becoming Halifaxâs own Johnnie Cochran â the American attorney best known for his role defending football player O.J. Simpson in a murder trial. Being the chief judge of the Provincial Court of Nova Scotia and the first African Nova Scotian to achieve that position was the furthest thing from his mind.

âFor a kid from North End Halifax and Newfoundland to become chief judge shows if I can do it, truly anyone can,â says Borden, who began his five-year appointment in August 2023. âI want to inspire those coming behind me.â

Borden started his criminology degree at Saint Maryâs University at age 21. He was the first person in his family to not only enter university but to graduate from high school, with the goal of becoming a corrections officer. While at Saint Maryâs, he worked full time at the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. One day, a colleague at the former orphanage asked him about his future plans. At the time, Burnley Allan âRockyâ Jones, ONS (BA â74, LLB â92), who would become a legend in the provinceâs legal system, was graduating from the Schulich School of Law. âYouâre as smart as Rocky,â his colleague said, encouraging him to aim high.

Borden applied to the law school's Indigenous Blacks and Miâkmaq Initiative, a program providing scholarships and mentorship to help students like him pursue careers in law. He was accepted and at age 27, he started classes. âI knew if I studied law, I could make a colossal difference in my community versus being a corrections officer,â he says.

But getting through the program wasnât easy or enjoyable. Although he felt like quitting at times, Professor Emeritus Rollie Thompson (â78) and mentor Doug Sparks encouraged him not to. âJust get your law degree and see what happens,â Sparks told him.

Eventually, Borden enjoyed the collegiality he shared with some law students and served as vice president of the ±«Óătv Black Law Studentsâ Association.

âThere are always challenges and opportunities, itâs what you do with those challenges and opportunities that makes the difference,â he shares.

While at law school, he met Halifax litigator Mary Jane McGinty through his involvement in a legal case centered on access to clean drinking water in the historic Black community of Upper Hammonds Plains. When he graduated, he took a job as an associate at McGinty McCleave law firm.

As a lawyer, he worked to improve access to justice and legal services for historically marginalized groups, serving on the Nova Scotia Barristersâ Societyâs racial equity committee.

In 2007, he joined the Public Prosecution Service motivated to work on more criminal cases. Within four months of becoming a Crown attorney, he was assigned a high-profile aggravated sexual assault and dangerous offender file. During the last five years of his prosecutorial career he worked in the special prosecutions service, focusing on cybercrime, child pornography and sexual assault offences. He became senior Crown attorney and held that position until he was appointed to the Bench in 2020, the same year he received the Queenâs Counsel designation.

âThrough my work in the Crownâs office I built a reputation of being fair but formidable,â he says. âI was known for prosecuting sexual offences. I knew I was making a difference for victims.â

Borden served as president of the Nova Scotia Crown Attorneys Association and in 2019, he led the Association in an acrimonious battle with the government over wages. He mentored numerous law students and initiated an articling program in the Public Prosecution Service. âThat is probably one of the proudest things I did as a Crown prosecutor,â he adds.

Born in Halifaxâs North End neighbourhood, Bordenâs father worked for the city driving dump trucks in the summer and plows in the winter. After his parents separated when he was five years old, he moved with his mother to Corner Brook, Nfld. For much of the time he lived there, he and his sister were the only Black people in the area. âI was different; I stood out,â he says. âI can remember somebody calling my sister the N-word walking home from lunch.â

Despite facing racism in Newfoundland, it was more overt when he moved back to Nova Scotia when he was 16. Borden had his first encounter with the law at age 18. Following a fight between young Black and white men in Halifax, he was charged with aggravated assault for a crime he didnât commit. âPolice didnât ask me my side of the story,â he says. âIt was an eye-opening experience. Just because the police say somebody did something doesnât mean that they did what they are alleged to have done.â

Borden went to court facing the accusations of four white people. âI took the stand and I gave my side of the story and told them who did it.â The hearing adjourned; the person Borden identified came forward and took responsibility for the crime.

Throughout his life, Borden has fostered his gift for bringing different groups of people together. He hasnât changed his approach since becoming chief judge. âI look for collaborative ways to make the system more efficient,â he says. âThat involves engaging various stakeholders.â

Currently, he is helping to establish the provinceâs first bail court in Halifax that will hear cases from across the province virtually. âNova Scotia is long overdue for a bail court. It is not uncommon to have dozens of accused individuals in custody every day,â he says. âHaving dedicated resources for bail hearings is a more efficient and effective approach that will have a positive impact on all areas of the criminal justice system.â

In his cherished time outside the courthouse, Borden cooks dishes like curry chicken and stewed beef for his wife and their teenage son. On most Sundays, they attend the Emmanuel Baptist Church in Upper Hammonds Plains and whenever he can, he turns off his phone and heads to the river by his home in Middle Sackville to fish.

Bordenâs appointment brings with it a new title, a new office and countless new responsibilities, but what is essential to him hasnât changed â standing up for his beliefs.

âMy entire life, Iâve been the guy rallying behind people, fighting for justice.â

Ìę

Recent News

- Schulich Law Students Win Impact Awards

- Professor Rob Currie ft in "Headed to the US? Lawyers are advised to take more precautions"

- Professors Dylag and Coughlan Awarded Law's Top Teaching Honours

- Professor Rob Currie ft in "If it comes to it, Canadian courts can and must be ready to resist U.S. annexation"

- Professor Emeritus Rollie Thompson ft in "Fixing family law"

- Schulich Law Grad Student Competes in 3âMinute Thesis Finals

- Meet the 2024â2025 Purdy Crawford Fellows

- Schulich Law Moves Up in Ranking of Worldâs Top Law Schools